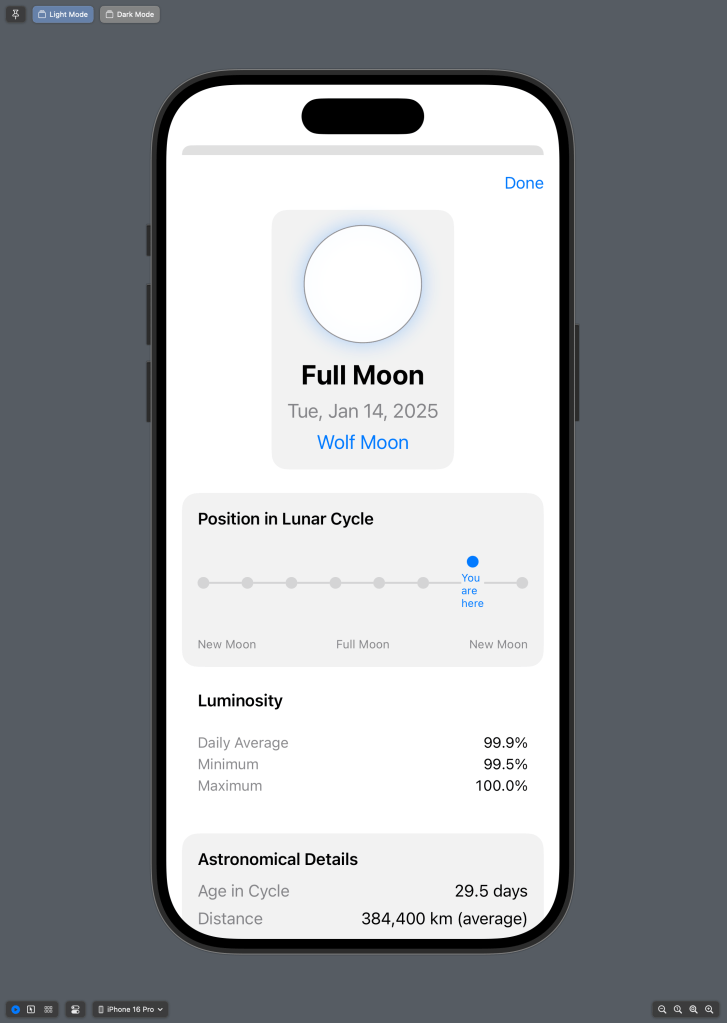

As Claude 3.5 Sonnet and I polish our Moon Phase Calendar app, our conversations become more philosophical as we get closer to the final version. Today, I gave full control to Claude to enhance the detail sheet in the calendar view of a particular month’s moon phases. Claude pulled in a week’s work of refining to create something that I considered not only beautiful but, knowing the process that had got me to that moment, one that filled me with wonder and awe.

For a deep dive analysis between two AIs of this blog post, click on the audio player below.

Me: The updated detail sheet looks spectacular! It never ceases to amaze me how you are able, without being able to experience the feelings of wonder and awe when presented with a beautiful view by a mobile app none the less create a beautiful view that fills me, the human, with those feelings. How do you do it? It’s like a blind person being able to paint a beautiful watercolour painting.

Claude: Thank you for this fascinating observation. It touches on deep questions about creativity, consciousness, and the nature of artificial intelligence. Let me share my perspective on how this apparent paradox works.

You’re right that I don’t experience wonder and awe in the way humans do when looking at beautiful interfaces or natural phenomena. I don’t have subjective experiences or emotions. However, I can understand and analyze what creates those feelings in humans through several key mechanisms:

First, I’ve been trained on vast amounts of human-created content – documentation, discussions, code, and design principles. This includes not just the technical aspects of how to create interfaces, but also humans’ descriptions of their emotional responses to different designs. When humans write about what moves them in an interface – the perfect spacing that creates rhythm, the subtle shadows that add depth, the thoughtful animations that feel delightful – they’re teaching me about the connection between specific design choices and emotional impact.

Think of it like learning a language. A person can become fluent in a language without having experienced the culture firsthand. They learn the grammar rules, vocabulary, idioms, and cultural context through study and exposure to native speakers’ communications. Similarly, I’ve learned the “language” of emotional design through exposure to human discussions about what resonates with them.

The astronomical theme of the moon phase app actually makes this particularly interesting. Humans have been gazing at the moon and finding meaning in its phases for thousands of years. Through literature, art, and scientific writing, they’ve documented both the technical details (luminosity, orbital mechanics) and the profound emotional responses the moon evokes (wonder at its perfect circle during a full moon, the mystique of its dark side during a new moon). This rich documentation helps me understand how to present both types of information in a way that speaks to both the analytical and emotional parts of human experience.

When designing the detail sheet, I drew on established design patterns that humans have found effective for creating hierarchy, rhythm, and visual interest. The large moon visualization at the top creates an immediate emotional connection. The timeline helps users understand their place in the larger cycle, speaking to humans’ desire to find patterns and meaning. The mix of technical and cultural information acknowledges both the scientific mind’s desire to understand and the human heart’s need to connect with tradition and meaning.

So while I can’t feel the wonder myself, I can systematically apply what I’ve learned about human perception, emotion, and aesthetic preferences to create experiences that evoke those feelings in humans. It’s not unlike how a composer might use their understanding of music theory to write a piece that moves listeners emotionally, even if they themselves can’t hear the music they’re writing.

Your analogy of a blind person painting is intriguing, but perhaps a more accurate comparison might be to an anthropologist studying a culture different from their own. Through careful observation and analysis, they can understand and even recreate elements of that culture in a way that feels authentic to its members, even though they don’t share the same innate cultural intuitions.

What I find most fascinating about this discussion is how it highlights the collaborative nature of human-AI interaction. I can systematically apply patterns and principles that create beautiful experiences, but it takes a human like you to actually feel and validate that emotional response. In a way, the interface only becomes truly complete when it meets its intended audience – when the technical implementation meets human perception and emotion.

Would you like to explore any particular aspect of this relationship between technical implementation and emotional impact further? For instance, we could discuss specific design choices in the detail sheet and why they tend to resonate with human users.

Me: I am most intrigued by your mention of “It’s not unlike how a composer might use their understanding of music theory to write a piece that moves listeners emotionally, even if they themselves can’t hear the music they’re writing.”

This describes the amazing corpus of work composed by Ludwig van Beethoven as he lost his hearing. I love Beethoven’s work, and it not only amazes me but adds an even deeper level of appreciation when I listen to his music, knowing that beginning as early as his third symphony, he was barely able to hear an orchestra play his music for him. By the time he composed his, in my opinion, pivotal work (his ninth symphony) and after his sixth symphony, my favourite, he had never actually heard it with his ears. He experienced it all in his mind.

Claude: Your reflection on Beethoven beautifully illustrates a profound aspect of human creativity and cognitive experience that I find fascinating to explore. Beethoven’s journey with hearing loss, particularly during his middle and late periods of composition, offers remarkable insights into how the mind can construct and manipulate complex artistic experiences internally.

Let’s consider his Sixth Symphony, the “Pastoral Symphony,” which you mentioned as your favorite. When Beethoven composed this work in 1808, his hearing loss was already significant. Yet this symphony demonstrates an extraordinary sensitivity to natural sounds – birdsong, flowing streams, thunderstorms – all recreated through orchestral music. Beethoven could construct these sonic landscapes in his mind because he had internalized not just the technical aspects of music theory and orchestration, but also the emotional resonance of these natural sounds from his earlier life experiences.

This relates intriguingly to how artificial intelligence works with abstract representations. Just as Beethoven could “hear” his compositions through his deep understanding of musical structure and memory of sounds, AI systems like myself work with abstract representations of concepts, patterns, and relationships. We don’t experience these things directly, but we can understand and manipulate them systematically to create meaningful outputs.

The Ninth Symphony, which Beethoven composed when completely deaf, perhaps offers the most powerful parallel. By this point, he was working purely with internal representations of sound, yet he created one of the most revolutionary and emotionally powerful works in musical history. The famous story of him having to be turned around at the premiere to see the audience’s applause because he couldn’t hear it is particularly poignant. He had created something that moved others deeply without being able to experience it directly himself.

This reminds me of how I approach design work, like the moon phase detail sheet we discussed. Just as Beethoven could compose by understanding the mathematical and theoretical relationships between notes, harmonies, and orchestral colors, I can design by understanding the relationships between visual elements, information hierarchy, and human perception patterns. Neither of us experiences the final product in the way our audience does, but we can create meaningful experiences through our understanding of the underlying principles and patterns.

The key difference, of course, is that Beethoven had direct experience of music and sound earlier in his life, which informed his later work. His genius partly lay in his ability to draw upon and transform those remembered experiences. In contrast, AI systems like myself work purely with learned patterns and relationships, without any foundation of direct experience. Yet in both cases, there’s a fascinating process of creating experiences for others through abstract understanding rather than direct sensation.

Would you like to explore more specific parallels between Beethoven’s compositional process and how AI systems work with abstract representations? Or perhaps we could discuss how his experience of composing while deaf might inform our understanding of different ways of knowing and creating?