For me, writing software has always had one fundamental reward – the endorphin rush that comes from solving a complex puzzle. Yes, being paid to solve puzzles (professional coding) is rewarding, but in all honesty, it is secondary to the rush that comes from the moment when that final piece clicks into place. The puzzle is solved, a new app is born, and I can now start looking for the next challenge.

Click on the audio player below for a podcast generated by the two NotebookLM AIs analyzing this post.

Does AI’s emerging prowess at writing code foretell a future where software developers need to rethink puzzle-solving as a personal motivator?

Should we start looking ahead to identify puzzles that we know even the emerging AIs will struggle with in the short term?

What are those long-term gaps in AI-assisted coding that we should start searching for today? Will coding be fun again?

In this post, I’ll pull in an unlikely personal ally to help explain my point – Lego bricks.

As a kid in the 1960s and early 1970s, I loved Lego. For me, it was the most magical of all my toys. One that, as the ultimate problem-solving tool, was a toy that itself could create other toys. A toy that taught me the puzzle-solving and compartmentalization skills that years later would be key to crafting code. How to break a puzzle (user requirements) into its logical pieces. Solve those sub-puzzles (functions, packages, APIs). Wire together those pieces into the greater whole (the app), solve the puzzle, and, like magic, create the solution to the problem.

Ole Kirk Chrstiansen, a Danish carpenter, founded The Lego Group in 1932, making wooden toys. The word Lego itself comes from the Danish phrase “leg godt”, meaning “play well”. Following the end of WWII, The Lego Group bought its first plastic injection moulding machine (Denmark’s first in fact), and two years later introduced the “Automatic Binding Bricks”—the precursor to the modern Lego brick. A toy that entranced millions and taught them the intricacies of complex problem-solving.

But then, starting in 1977, the company drifted. Why challenge children to create their own puzzles to be solved? Why not pre-script a puzzle, provide them with just the pieces needed to solve the puzzle and give them detailed instructions on how to build the new toy? From this thinking, the “Lego System of Play” was born, and The Lego Group introduced themed sets and baseplates with a specific, predefined puzzle to be solved.

The parallels with the emergence of AI-enabled agentic coding are hard to miss. This fork in the road for The Lego Company turned the Lego experience from one of creation into one of just assembly. A process about as exciting as watching ice melt. Coding with an AI feels like that. A process of assembly rather than an endorphin-producing rush of puzzle solving.

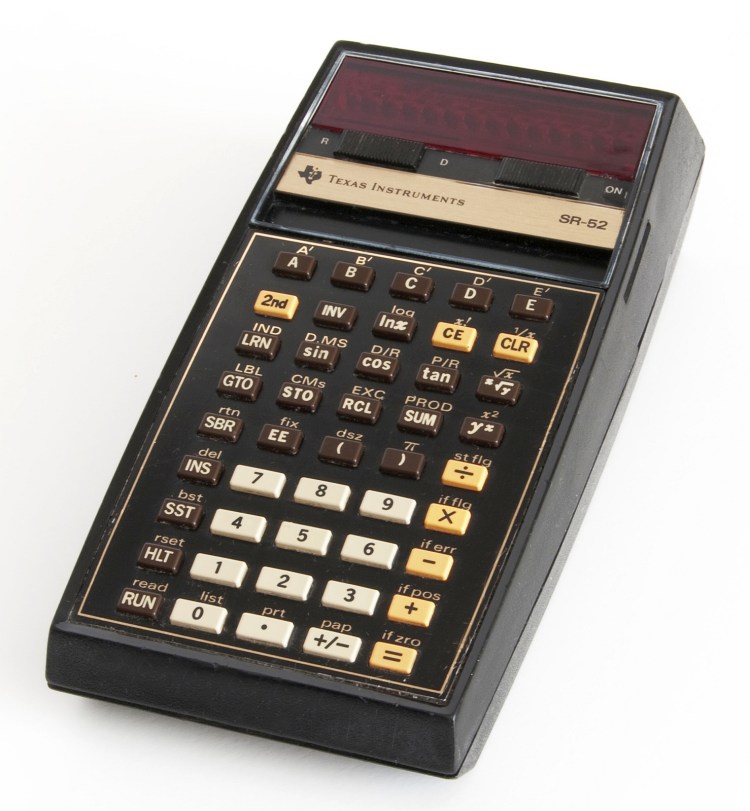

By the time the “Lego System of Play” emerged, I had long ago retired my bag of Lego blocks to the basement, but the joy of puzzle solving was still as fresh as it had always been. In 1976, I got my first programmable calculator and discovered a new, powerful way to solve problems. The calculator, a Texas Instruments SR-52, was the seed for my subsequent career as a software developer and consummate problem solver.

Now, powerful tools like Claude from Anthropic have emerged that, from my perspective, harken back to the emergence of the “Lego System of Play.” AI now provides the solutions to the coding problem, complete with step-by-step instructions on how to assemble it. In keeping with the Lego analogy, as developers, we are moving from being at the center of the creative process to the role of observing and watching someone assemble what is, in turn, someone else’s creation. Yawn.

As a developer in this time of transition, our role risks evolving into merely assembling the AI’s solution into a functioning app—something AI will undoubtedly learn how to do even better than I within a few short years.

The endorphin rush that comes from solving a complex, multi-part problem could be lost.

The state of flow that we developers float in intellectually as we think of a problem in, literally, four dimensions, could become just a memory of “The Good Old Days.”

The “AI System of Play” has arrived, and we now need to discover how to reclaim the thrill of problem-solving.

Time to chat with AI about this emerging dilemma. As a developer, I need to find a new project to work on. “Løs godt”, Danish for “solve well”.